My husband and I fell in love and got married quicker than you can say “Who moved my cheese?”

Almost as quickly, if not quicker, we got pregnant with our first kid.

We didn’t take the time to have the important parenting conversations like,

“Do you mind if our kids eat candy for breakfast?”

“Is it important that our kids go to college? Or is GED good enough?”

“Is it okay if our son marries his cousin?”

Somehow, we’ve made it this far without divorcing or selling one of our children on the black market.

Eventually, we had a lot of those crucial conversations, and luckily see eye-to-eye on most parenting issues.

Our values line up.

When we disagree, I can usually persuade him. Sometimes it takes a few years…Like the time he refused to switch from Heinz ketchup to the organic Whole Foods brand.

Three years later the organic brand was in our fridge door.

(Now, in Israel, we’re back to Heinz. It’s a specialty item, which in Hebrew means “practically organic.”)

There was this one time, however, when my husband was right in the first place.

We were talking about our kids as teenagers and how comfortable we would feel if one of them decided to dress “Goth.”

My husband was insistent that we would be flexible about piercings and black lipstick and long leather jackets. He said we needed to foster their sense of creativity and self expression.

I could see his point, though I was hesitant and reluctant.

Truth is: I don’t want my kid to be the kid teachers and other kids are afraid of.

Also, I’ve never been good at not being scared of people who dress scary.

I don’t want to be scared of my own kid.

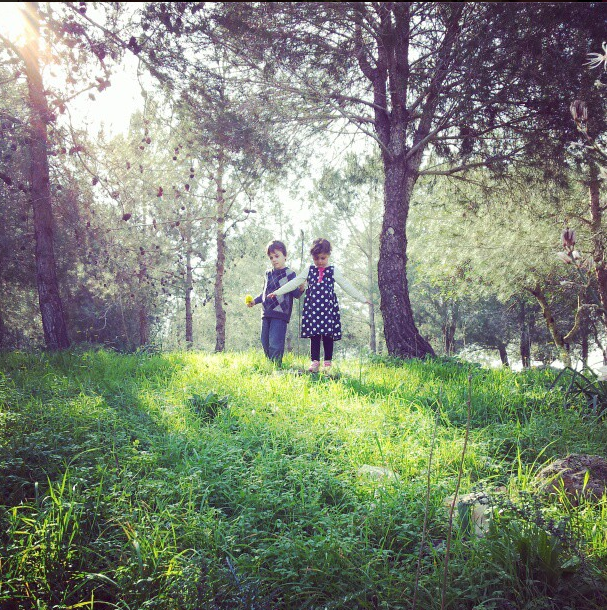

Our kids are still too young to be expressing themselves with their outerwear just yet, but one day a year, my oldest son wants to show off his dark side.

Purim.

The other kids come to the bus stop in homemade Mordechai costumes, or walking clever references to pop culture.

But my kid?

Year after year, he wants to scare the bejeezus out of you.

My husband usually goes along with it.

But this year, concerning the above nail-impaled zombie mask, my husband was himself reluctant.

At first, he considering forbidding my son to wear the mask. (It was a gift from Saba and Savta.)

It’s not appropriate, my husband told me. Purim is not Halloween.

He’s right.

Or at least maybe he’s right.

Who am I to know what’s Purim appropriate? I’m still a Jew in progress. Still an immigrant mom. Still figuring out how not to embarrass myself on a daily basis.

But what I do know — what I’m sure of — is that my husband was right when we first had that conversation 8 or 9 years ago.

We absolutely, positively want our children to feel free to express themselves.

As long as they aren’t hurting themselves, or others, we want them to be comfortable showing the world who they are.

To dance.

To sing.

To frolic.

To feast.

To be free.

This is Purim spirit, I’m sure of it.

This much I know.